Often, we assume that increasing college graduate rates is worth the investment needed to spur that growth. The «ÔŅŻ ”∆Ķ decided to put an economist on the job of figuring out whether that's true. In a report titled, "The Economic Impact of Increasing College Completion," a team of analysts from attempted to lay out the costs and benefits of a sustained investment program aimed at boosting program completion rates, especially for disadvantaged students. The bottom line: The investment would hurt in the beginning but pay off in big ways down the road.

The analysts likened the venture to the building of the interstate highway system in the 1950s and 1960s, which "imposed considerable costs on the American economy as well as creating significant disruptions and dislocations during the construction period." Over time, however, "the speed and reliability of travel" increased dramatically, "yielding economic benefits that far outweighed the costs."

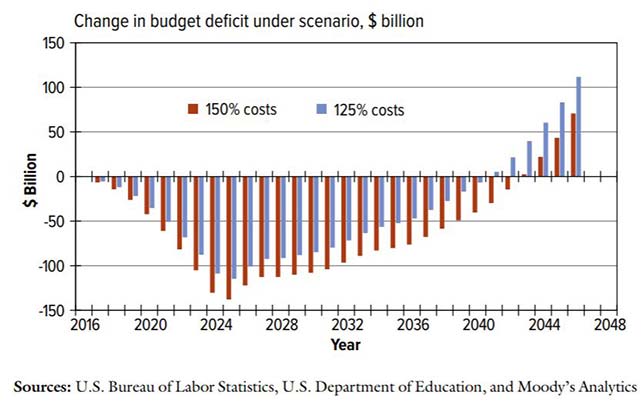

Effect on budget deficit. Source: The «ÔŅŻ ”∆Ķ' report, "The Economic Impact of Increasing College Completion"

The model used several assumptions, pulled from results generated by specific college completion programs:

- The graduation rates of students now in the bottom half of the distribution of institutional graduation rates would rise by 50 percent and the graduation rate of those in the top half would grow by a "somewhat smaller percentage."

- Improvements would be phased in over a 10-year period, during which the graduation rates would grow gradually. For example, a school with a 40 percent graduation rate would rise to 60 percent over the 10 years.

To estimate the cost of implementing the various college completion programs, the analysts went with two sets of assumptions, one where the costs would rise by 50 percent per student to achieve the improvement, and another where the costs would only rise by 25 percent. As the report explained, those numbers are consistent with the experiences of programs where completion rates have grown substantially.

During the first 10 years, the report stated, the costs of the investments "substantially outweigh the benefits generated by the additional students who have completed their programs."

However, that scenario turns around as the productivity benefits of the workers who have acquired their college degrees begin to grow. As a start, younger students who have entered the workforce for the first time as "college completers" bring more education and higher productivity than the less educated workers who are retiring from the labor force. The same logic applies, the report observed, to non-traditional students who have decided to return to or obtain their college degrees too since they earn more money and produce more output than before.

By year 11 of the program, the cost-benefit balance begins turning around. "In every year thereafter output and earnings in the economy are higher than they would have been without the investment," the analysts asserted. In fact, by year 30, average wages in the workforce would be about 3.1 percent higher than they would be without the investment, with the gains focused on those who wouldn't have achieved degrees without the program.

Looking 20 to 30 years out, when the net benefits of the program are fully in place, the analysts calculated that annual gross domestic growth would be about 10 percent higher than it would be without the program (1.9 percent vs. 2.1 percent) ‚ÄĒ benefits that would continue "well beyond 2040, with the net benefits of the program continuing to grow."

"In purely economic terms, a program of investment in higher education imposes net costs on the economy in the near term ‚ÄĒ costs that can be financed by government or private borrowing or by higher taxes," the report concluded. "But as the education level of the workforce rises, so do earnings and output. After a number of years, the economy is more productive, and employment and GDP are larger than they would have been without the investment ‚ÄĒ large enough, in fact, to pay off the earlier borrowing or provide sufficient income to pay for the higher taxes."

In other words, the analysts noted, students taking time out of the workforce to pursue their degrees will "typically receive an earnings benefit" that will last for 30 to 40 years. That's a longer period, the authors pointed out, "than most bridges or highways last."