There’s a new resource in town for science advocates, communicators, researchers and others with an interest in understanding what the public thinks about science. The compendium from the American ÇďżűĘÓƵ of Arts and Sciences pulls together data from public opinion surveys on public trust in science and scientists to highlight three key points that are often forgotten or misunderstood.

First, in contrast to views of other institutions, public confidence in scientific leaders has remained stable since the 1970s, according to data from the General Social Survey conducted by the NORC at the University of Chicago. But the breadth of the scientific enterprise and the lack of consensus about the boundaries of science often lead to a more complicated portrait of public opinion. For example, an exploratory market research survey from ScienceCounts, a non-profit aiming to enhance public support for federally-funded scientific research, finds a sizeable minority of the public (42 percent) has no trust or not too much trust that scientists will report findings even if the findings go against the sponsor of the research.

.jpg)

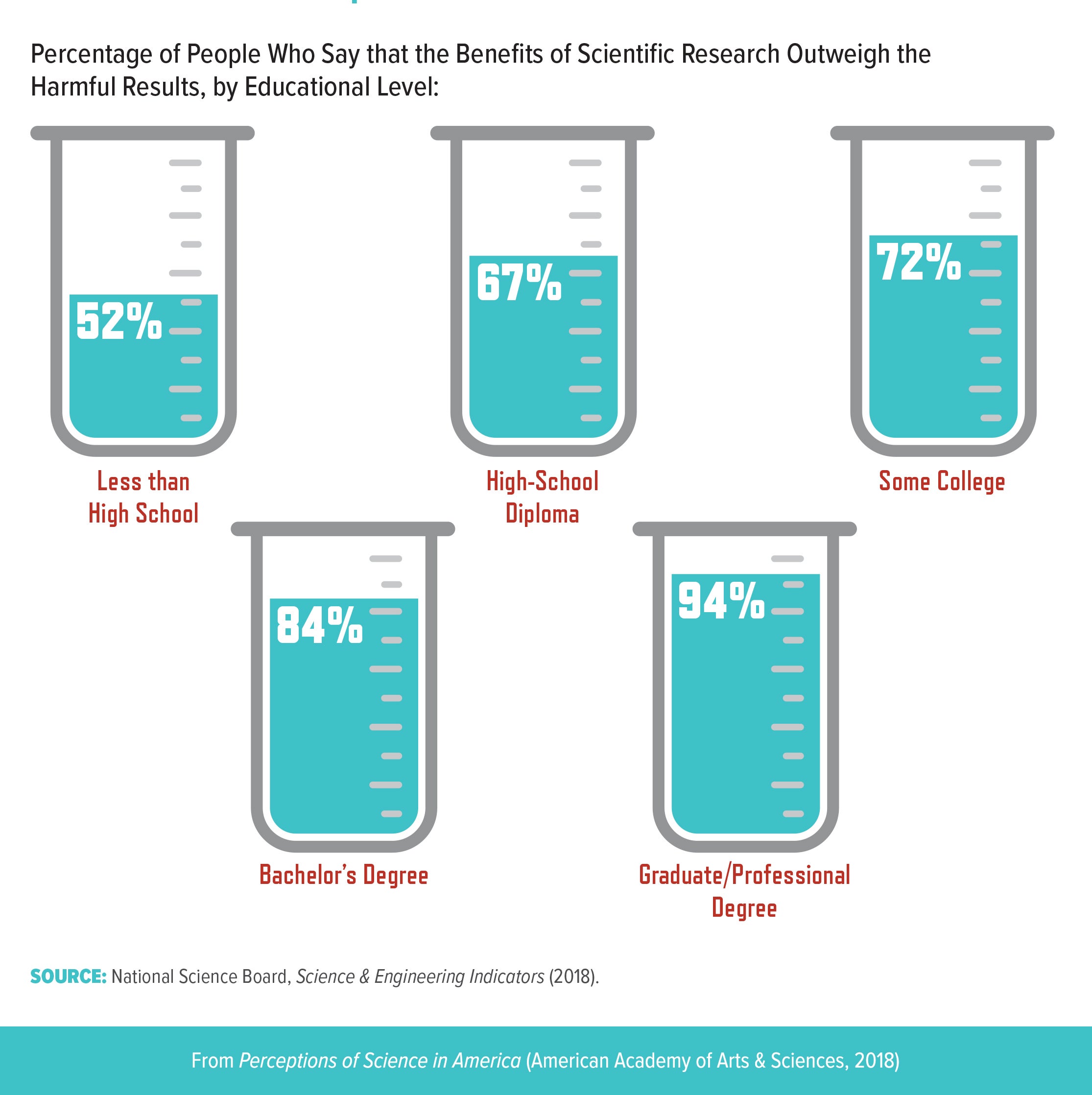

Second, time and again in surveys, there are important differences among subgroups of the public in the degree to which they trust science and support scientific research. The scientific community would do well to remember that “the public” is not monolithic—age, race and ethnicity, political viewpoints and levels of education influence people’s opinions. Just one example from the 2016 General Social Survey conducted on behalf of the National Science Board, fully 94 percent of Americans with a postgraduate degree think the benefits of scientific research outweigh the harmful results compared with about half (52 percent) of those who have not completed high school.

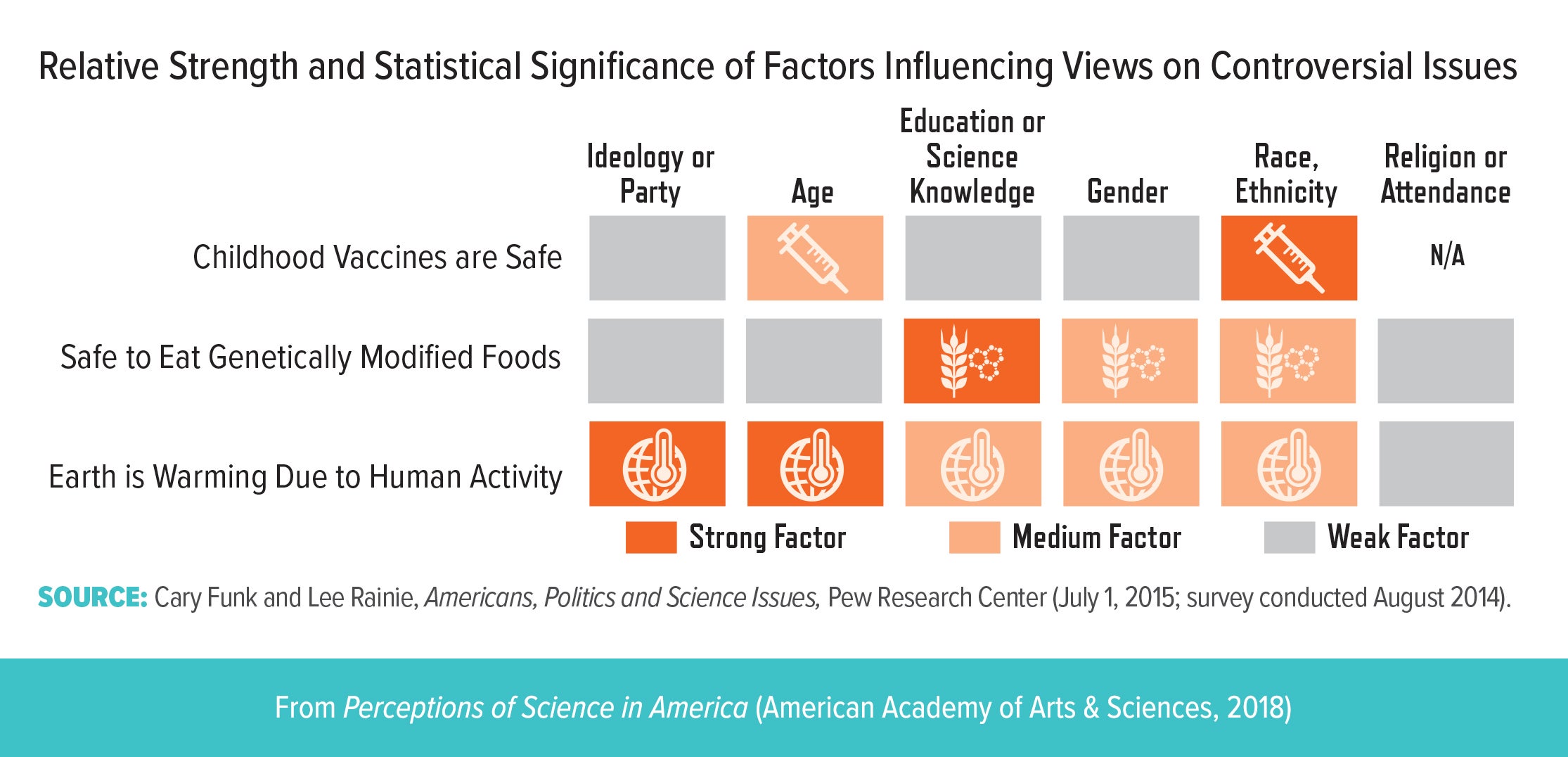

Third, there is no single “anti-science” demographic group. While more research is needed to better understand what drives skepticism among some in the public about scientific evidence or scientific consensus, past studies have shown no single background factor such as politics, education, age, race/ethnicity, gender or region consistently predicts who among the public is more skeptical of prevailing scientific consensus.

On climate and energy issues, people’s views are strongly connected with their political identities but views about the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine and eating genetically modified foods are not, according to Pew Research Center studies. And people’s group identities – whether rooted in politics or some other identity – can influence how people integrate knowledge and understanding about science into their beliefs. The next generation of research on these topics hopes to better understand how and why this occurs.

The American ÇďżűĘÓƵ embarked on this report with a stellar steering committee and a range of advisers to address what they describe as the “complex and evolving relationship between scientists and the public.” The ÇďżűĘÓƵ plans to delve into how people encounter science in their daily lives and offer recommendations for science communication and engagement down the road. Until then, Perceptions of Science in America offers a rare synthesis of current understanding about public perceptions of science as well as the gaps in that understanding.

One thing is already clear from this roadmap. Those wishing to better grasp public thinking about science need to look beyond trust in “science” writ large to see how people make sense of the science issues and domains which connect with their lives—such as childhood vaccines, genetically modified foods, and climate change—and think beyond one “public” to the reasons for pockets of support and resistance to scientific evidence among the populace.